Logic Games to be Removed from LSAT

By: Ashley Harunaga

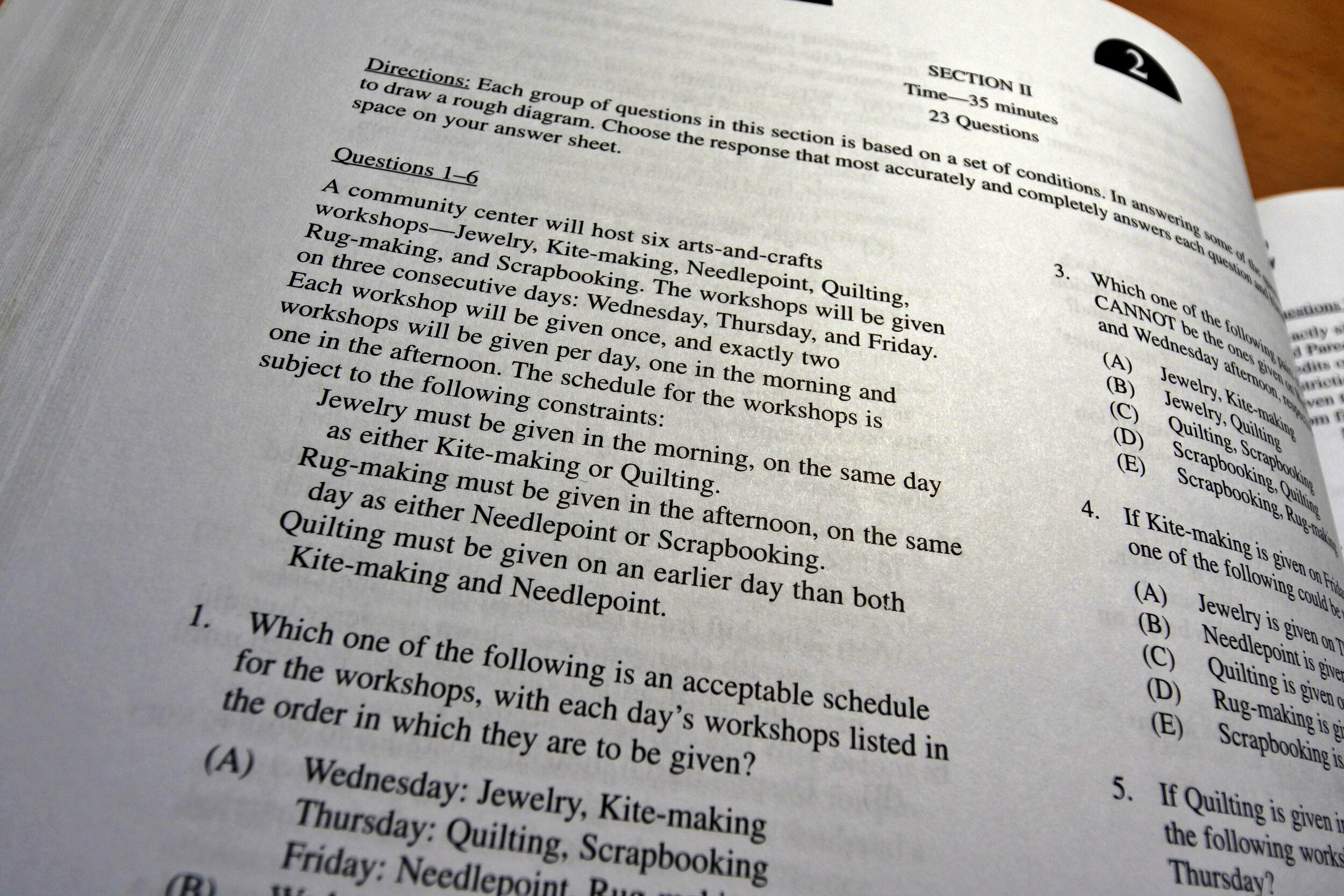

The Law School Admission Council (LSAC) has reached a settlement with two vision-impaired test takers to remove the logic games section from the Law School Admissions Test (LSAT) within the next four years. The LSAT is the primary standardized test used by law school admissions departments and is comprised of four sections: logic games, logical reasoning, reading comprehension and a writing section.

The initial lawsuit began in 2011 after Angelo Binno, a blind prospective law student, took the LSAT twice and was dissatisfied with his experiences. LSAC provided accommodations but denied to waive his logic games section. He filed a lawsuit against the American Bar Association (ABA) and was represented by Richard Bernstein, now the first legally blind Michigan Supreme Court Justice.

Binno argued that one-quarter of the LSAT is completely inaccessible, no matter the type of accommodations given to someone who is blind. In 2014, Bernstein was elected to the Michigan Supreme Court. So, Jason Turkish, who is also visually-impaired, took over as lead counsel.

“They are still not going to be able to draw the diagrams no matter how much time they are given,” said Binno’s second attorney, Jason Turkish. Turkish is a Managing Partner at Nyman Turkish PC, a national litigation and disability law firm. “The test isn’t testing Angelo on his aptitude for the study of law, it’s testing his ability to do something he physically can’t –– draw pictures,” said Turkish.

Binno filed suit against the ABA arguing that their accreditation rules violated Title 3 of the Americans with Disabilities Act. Title 3 proscribes entities from offering discriminatory exams. This case was dismissed on standing grounds, essentially deciding that the ABA didn’t offer the exam, they just required it. The dismissal was affirmed by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals.

After Turkish took over Binno’s case against the ABA, they filed a petition for certiorari in the Supreme Court that was ultimately denied.

“I remember after arguing the case in the U.S. Court of Appeals promising Angelo and his family that we would not stop until we found a way forward, and for us that couldn’t be the end of the case. Too much was at stake,” said Turkish. “Not just for Angelo to participate in the process, but also making sure there’s another generation of civil rights lawyers who are blind. Making sure that Richard Bernstein isn’t our last state Supreme Court Justice. So it was back to the drawing board.”

In 2017, Binno filed a new case in federal court in Detroit against the LSAC. Shelesha Taylor was similarly situated as a significantly near-point visually-impaired person and moved to intervene as an additional plaintiff in the lawsuit. Rather than continuing to litigate, on October 7, 2019, LSAC and Binno were able to settle in a “very profound way that is going to result in change nationwide for everybody,” said Turkish. “I'm really proud of [Binno] sticking with it all these years.” At that point, Binno had been in court for nearly six years.

This case differed from a handful of other cases against the ABA because Binno and Taylor’s lawsuit actually challenged the “existence of the test as a discriminatory examination,” said Turkish. This was not saying the LSAC failed to provide a reasonable accommodation. Rather, it was saying that this test simply cannot be accommodated for visually-impaired test-takers. Therefore, the only thing that could be done is “eliminate it to fairly accommodate someone who is blind,” said Turkish. “It simply on its face is discriminatory.”

Given the sensitive nature of the settlement, LSAC declined a request to be interviewed, but released a statement. The parties in the lawsuit have agreed to “research and develop alternative ways to assess analytical reasoning skills … to determine how the fundamental skills for success in law school can be reliably assessed in ways that offer improved accessibility for all test takers.” They promise to “complete this work within the next four years,” since analytical reasoning is an important skill that they want to continue testing in some way. They are “simply redesigning the way in which that skill is assessed.”

Bryan Hinkle, Assistant Dean of Law Admissions and Financial Aid at Santa Clara University School of Law, said “we probably won’t get any sort of update [soon].” “We don’t know if or how this will change the scoring of the test.”

However, Turkish remains hopeful for the future. Turkish said, “for folks who can’t see, the LSAT could really shut the door completely on them. I really think the number of blind law school applicants will shoot up which is a really fantastic thing.”

“When you shut out people like Angelo from the process, you’re not just shutting them out from law school. You're shutting them out from being champions and leaders for civil rights calls on behalf of the next generation,” explained Turkish. Victory here in this settlement is not only for Angelo, but disabled future leaders in society, he said. Turkish added, “this is one of the biggest changes to the LSAC in almost 30 years.”

(Editor's Note: This article was originally published in the December 2019 [Volume 50, Issue 2] version of The Advocate.)